An Interview with Professor Noriaki Kano

CQI Head of Profession Mike Turner, spoke to world-renowned TQM and quality management guru Professor Noriaki Kano.

Last month I had the honour and pleasure to interview Professor Noriaki Kano. Students and practitioners in quality management will be very familiar with Professor Kano’s work, particularly in the field of understanding customer behaviour

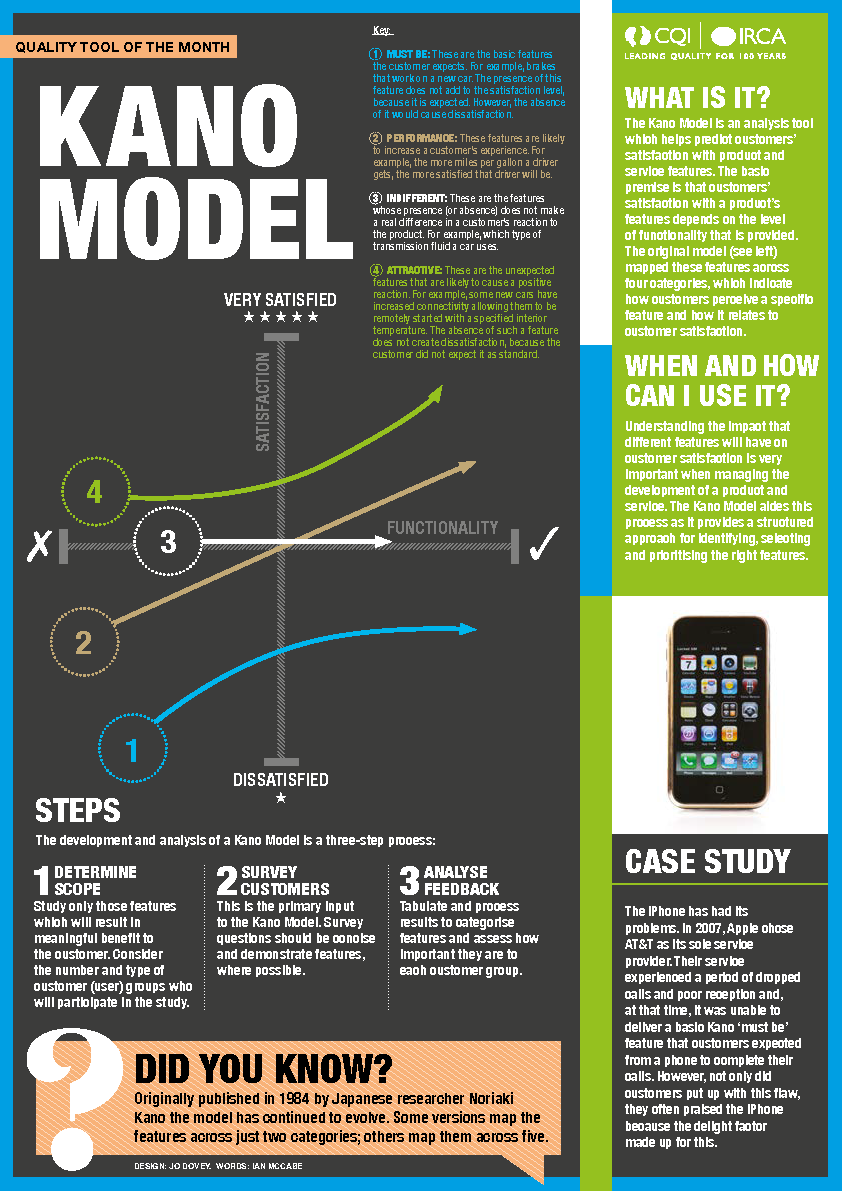

One of his best known contributions to the development of quality management is the Kano model. It was there that I began our conversation. I wanted to hear how he had developed what is such a powerful and enduring model.

The need for the Kano model

Professor Kano took me through a brief history of the development of this model, starting with his first interest in quality management.

From a very young age, he was fascinated with how things were designed and made to be reliable and serviceable. This interest led him to pursue an academic career at the University of Tokyo during which he had the privilege of studying under Professor Kaoru Ishikawa, another major contributor to quality management theory and practice, particularly in the area of quality circles.

It was during this time that Professor Kano explored the importance of defect-free supply to what defines ‘quality’ and hence the need to understand how the customer judges quality and identifies defects. At that same time the impact of the quality circles approach was establishing Japan’s reputation for supplying quality products.

The roots of the model - a study of quality circles

Alerted to this growing competitive advantage, engineers from Lockheed Corporation visited Japan in the early 1970’s with the objective of understanding enough of the quality circles approach to implement it in their US west-coast facilities. However, the practice did not seem to wholly and successfully transfer to the Lockheed US setting prompting a request for help from the University of Electro-Communications. Associate Professor Kano was nominated to travel to the USA to identify the reasons for this limited success. He concluded that unlike Japan, where quality circles were managed by engineers, the US approach was led by people working in the fields of behavioral science and industrial psychology. The US approach was less focused on the mechanics of the approach and more on motivating workers to engage in the new practices.

As a consequence, Professor Kano began further study into the theories of motivation at work, which led him to explore Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs model and Herzberg’s theory of the distinction between hygiene factors and motivators. Taking these discoveries and relating them back to his original enquiry into the ways in which customers judge quality led him to explore whether some aspects of motivation theory could translate into customer buying behavior and the antecedents of satisfaction. The roots of the Kano model were by now established.

Substantiating the Model - Overcoming the hurdles of peer acceptance

He then commenced a research programme that investigated whether it was possible to differentiate between “must have” features of Quality and “attractional” features of Quality, as seen in the eyes of the customer. With great humility, Professor Kano then explained that his academic peers rejected this initial research on the basis that his underlying hypothesis was insufficient. It was considered too simplistic and did not provide sufficient basis for the range of behavioral responses that he had discovered through his research.

The next stage of this story was quite fascinating. A lady named Yoko Ono (her current name is Yoko Oyama) was, at that time, working as a secretary to Professor Kano. Whilst at the Department of Philosophy at the Tokyo Woman’s Christian University she had studied a work of the Greek philosopher Arsitotle entitled ‘Metaphysics’ in which the philosopher discusses the nature of things and how to differentiate them. In Volume 5, Chapter 14 Aristotle explores the Greek word "Poion", a questioning adjective that describes the nature of something; for example how to describe what ‘kind’ is something. It is from this term that the abstract noun 'poiotes' is derived, which is translated as ‘quality’. Aristotle argued that the nature of a thing is a " difference of aspects” (i.e. a species difference). For example, if we ask "what kind of nature is man," we would say "the two-legged one" and if we ask "what kind of nature is the horse," we would say "the four-legged one”. Extending this concept of the difference of aspects provides the basis to understanding the difference between “good” and “bad”.

At that time, Professor Kano was wondering whether quality factors such as "safety", "remote control" and "image quality" should be treated as the same level of (comparable) "quality" or not. He concluded that Aristotle's definition of "quality as a species difference" gave him the approval to treat them equally as aspects of quality. This made it possible for Professor Kano’s research to classify the different ‘quality’ elements that form the basis for the Kano Model e.g. ‘must be’ quality, one-dimensional quality, etc.

A timeless model

Why have I included this explanation in my write up? For me, this is a great example of how an enquiring mind, perseverance, collegiate working and an ability to adapt theories from other disciplines contributed to the development of a model that has enduring value.

If we think about some of the challenges of a world in which digital technologies are having a significant effect on the way in which customers define, configure, consume and redefine value, this model has a very important role to play in managing such engagement. It is because it is grounded in fundamentals of science, engineering, philosophy and psychology that it has stood the test of time, and not become a transient “fad”.

Challenging Quality 4.0

The second part of our discussion focused on Professor Kano’s views on the future of Quality. His response to the challenge of Quality 4.0 was to offer a counter challenge. In order to describe Quality 4.0 one must be able to describe each of the stages of Quality 1.0 through to 3.0, what changed along the time line and what value each stage contributed. Unless we do this, we are open to the development of new approaches driven more by conjecture than fact. He illustrated this with a challenge to the theoretical basis for the Six Sigma approach and the DMAIC method. Professor Kano argued that the method of quality circles, which pre-existed Six Sigma, and was based on thorough and rigorous research, remains universally applicable and did not need a new approach invented. His point here is the need for continuous development of theory and practice, as opposed to discontinuous development. The latter may suit the desire for innovation but can be open to circumstantial or prejudicial bias. Value is lost when it is applied to a different setting to that is which it was developed.

Understanding Big Data

He also touched on the subject of Big Data. His view is that the world has become confused as to the different sources and treatment of data, and can apply inappropriate approaches to analytics. He contrasted data extracted from a standardised process from that captured from a broader societal base. The former is characterised by less sources of variation, narrow in scope and attributable to the design of the process. The latter is characterised by greater sources of variation, broader in scope and unattributable to one framework. The treatment of these data must differ and the

analytical method should be based on these characteristics else conclusions could be misleading or false.

A view of the future of quality

This discussion has led to some important learning points in our quest to explore the future of quality management. Firstly, there does not seem to be an accepted definition of Quality 4.0 and the question as to the value of gaining one is still open. We, the CQI, intend to address this as the first part of our journey of discovery into the future of Quality. Secondly, we must be cognisant of the risk of discontinuous and biased development of Quality 4.0 principles and practices else we risk developing something of limited and transient value; the next ‘fad’. Finally, we must be rigorous in our selection of and application of Quality 4.0 tools, driven by adherence to the core concepts of quality management and not by what seems to be fashionable and attractive.

However, on reflection there is a risk against which we should guard. The practice of rigorously pursuing product and process performance excellence through the detailed application of quality improvement tools undoubtedly has merit, but there is also the need for a broader view of contextual factors that could impact the design of, and even need for the product or process. We can all cite examples where, in some industries, whole product categories or even businesses have perished for the lack of an eye on, and a response to competitive dynamics. And so we return to the Kano model. Surely, in times such as we now face in the world, a robust and well-research model that leads managers to analyse what customers really value, in all aspects of what constitutes ‘quality’ is ever more vital. It should be exactly this that protects engineers, managers and quality professionals from an overly detailed view. Is this the time for a resurgence of the Kano model?

Review the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy