From ineffective auditing to effective auditing

Progress indicator

Stephen Asbury talks about behaviours to avoid and tips to improve your auditing skills

As Managing Director of a registered certification body, an IRCA Lead Auditor, I have observed the practice of many health, safety, environment and quality (HSEQ) auditors. I was often left feeling unimpressed by what I saw and it got me thinking about the common behaviours and characteristics that I’ve seen in my time, which represent ineffective auditing. Below is a table that outlines 10 common incorrect ways of dealing with audits and my tips for how to improve. The aim of the table is to challenge you (if you are an auditor that ticks any of the wrong charateristics) to demonstrate the improvement messages. If you are not an auditor, I challenge you to hold those who audit you to these same messages.

| # | Wrong behaviour/characteristic | Tips for improvement |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | An audit is not an ‘inspection’ and should not be conducted like one. | Use ISO 19011 for process. There is a new version of this standard coming this summer – use it to guide and support your process. Take a high-level approach to understanding the context (ISO Annex SL, Clause 4), the organisation’s objectives and its significant risks (impacts on objectives, from ISO 31000). A trailing cable is not a finding in a management system audit. |

| 2 | The auditor was obsessed with the clauses of the standard. | The audit workplan should focus on a sample of significant risks. These may arise externally, internally, or as a result of the views of interested parties. |

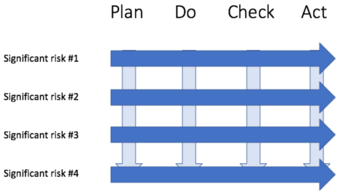

| 3 | The audit was conducted vertically – it progressed through the standard’s clauses in turn – Leadership, tick; Planning, tick; Roles, tick. | The audit should progress horizontally (see Figure 1) through the structured means of control (plan, do check, act) for each risk in the workplan. |

| 4 | Reinventing the reference framework. | The auditor must understand ISO Annex SL and the specifics of the management system (MS) reference framework they are using for their audit. Housekeeping is not a finding in an MS audit. |

| 5 | ‘Blue Peter’ evidence (ie, ones we made earlier). | An audit should provide an independent view of the status of control of workplan risks. The auditor is responsible for structuring a sample of audit tests using (up to) six key testing techniques – known as C-COVER. The auditor should adopt a Gemba attitude throughout. |

| 6 | The auditor said: “You are not performing well enough.” The auditee disagreed. | Report the facts as you found them – eg, six from a sample of 10 were incomplete. Audit is a mirror – it reflects the status of control through a sample of significant risks. The auditee should recognise their organisation in the reflection provided by the auditor. |

| 7 | The auditors made some of the managers feel that they had personally let the organisation down. | Audit is confidential (refer to ISO 19011). Be like a journalist – don’t reveal your source. |

| 8 | The auditee was embarrassed in front of their colleagues at the closing meeting. | Maintain a Nemawashi approach throughout to secure buy-in and support for your audit findings. |

| 9 | There were so many low-level, trivial findings. | At the closing meeting with the auditee’s senior management, the auditor should present a high-level, future-facing audit report. For instance, “If you manage significant risks like this, we predict ‘x’ (your audit opinion) will be the outcome”. |

| 10 | The auditee did not like the auditor or value the audit experience. | Develop rapport with your auditee – positive engagement/interest with another human. Provide an audit service so well-grounded in facts that the results are acknowledged, accepted and acted upon irrespective of how unpalatable they may be. |

Effective risk-based audits add value to themed or integrated management system implementations. Case studies and experience demonstrates that structured approaches to HSEQ risk management is more effective at mitigating losses and maximising opportunities. And there is considerable opportunity. For example, the International Labour Organization (ILO) reports that every 15 seconds a worker dies from a work-related accident or disease and more than 150 are injured. By focusing on a structured sample of significant risks and using competent auditing techniques, auditors can demonstrate their value to their organisations, clients and society.

Figure 1 – Selection of significant risks to the achievement of the auditee’s objectives leads to review and testing of the management system horizontally through the PDCA cycle.

About the author: Stephen Asbury, MBA FIEMA, PEA CEnv CFIOSH, Author of Health and Safety, Environment and Quality Audits – A Risk-based Approach

Get your copy

Health and Safety, Environment and Quality Audits – A Risk-based Approach. For a chance to win a copy of a book, email [email protected] with ‘HSEQ book comp’ in the subject line and tell us how many pages the book has. THIS COMPETITION IS NOW CLOSED. THANK YOU TO ALL THAT PARTICIPATED.

Quality World

Get the latest news, interviews and features on quality in our industry leading magazine.