Time to challenge and reshape the cost of quality paradigms

Progress indicator

Bob Goodwin, CQP MCQI MSc PGDip, explains why the cost of quality should not be the main focus for quality professionals

Businesses typically use the phrase ‘the cost of quality’. But what does it actually mean?

Does it mean the cost of the quality function? The cost of the business infrastructure (trained employees, tools, environment, business processes etc)? The checks, reviews and inspections carried out during the businesses processes? Or the costs incurred to all when things have gone wrong?

There are many more, but in simple terms most of these are the underlying elements of the widely used Prevention, Appraisal and Failure (PAF) cost model.

According to the American Society for Quality (ASQ), prevention costs are incurred to prevent or avoid quality problems. These costs are associated with the design, implementation, and maintenance of the quality management system. They are planned and incurred before actual operation, and could include:

- Product or service requirements – Establishment of specifications for incoming materials, processes, finished products, and services.

- Quality planning – Creation of plans for quality, reliability, operations, production, and inspection.

- Quality assurance: Creation and maintenance of the quality system.

- Training: Development, preparation, and maintenance of programmes.

Appraisal costs are associated with measuring and monitoring activities related to quality. These costs are associated with the suppliers’ and customers’ evaluation of purchased materials, processes, products, and services to ensure that they conform to specifications. They could include:

- Verification: Checking of incoming material, process and products against agreed specifications.

- Quality audits: Confirmation that the quality system is functioning correctly.

- Supplier rating: Assessment and approval of suppliers of products and services.

Internal failure costs are incurred to remedy defects discovered before the product or service is delivered to the customer. These costs occur when the results of work fail to reach design quality standards and are detected before they are transferred to the customer. They could include:

- Waste: Performance of unnecessary work or holding of stock as a result of errors, poor organisation, or communication.

- Scrap: Defective product or material that cannot be repaired, used or sold.

- Rework or rectification: Correction of defective material or errors.

- Failure analysis: Activity required to establish the causes of internal product or service failure.

External failure costs are incurred to remedy defects discovered by customers. These costs occur when products or services that fail to reach design quality standards are not detected until after transfer to the customer. They could include:

- Repairs and servicing of both returned products and those in the field.

- Warranty claims: Failed products that are replaced or services that are reperformed under a guarantee.

- Complaints: All work and costs associated with handling and servicing customers’ complaints.

- Returns: Handling and investigation of rejected or recalled products, including transport costs.

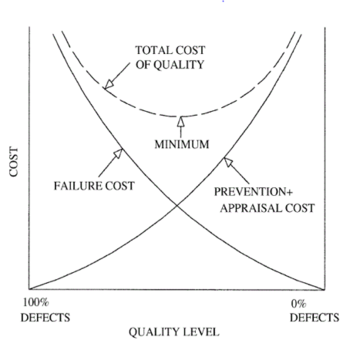

Alongside the PAF model is the ‘thinking on business finance’. The general view is that there is a balance to be struck between applying activities to assure quality and the subsequent cost to the business and the actual costs of failure (see graph below).

You will see from the graph that it refers to ‘quality level’ and seems to suggest that achieving zero defects is costly and that the minimum point of financial cost to the business is where cost of prevention equals cost of failures. This harks back to the days of ‘acceptable quality levels’ and ‘sampling plans’ where some degree of defect was almost expected and deemed ‘acceptable’. However, shouldn’t our aim be zero defects?

Many businesses regularly report the PAF cost of quality as part of management reporting and, if all these elements are accounted for, this can be a truly significant figure. But is this cost analysis actually meaningful?

Let’s assume a business is in business to meet customers’ needs, make a profit and to be sustainable ie, it believes in providing a quality product or service such that customers get value, are happy to pay the asking price and will hopefully return for more. A business also aims to be available to provide ongoing customer support. It could be argued that if a business wishes to endure (and what business does not wish to endure?), then providing a quality product or service is just ‘doing business’.

Let’s also assume that most people go to work to do a good job. Designers to design products that are reliable, safe, fit for the purpose claimed and expected; manufacturers create products that meet the design specifications, are built with care using the specified components etc; sales staff sell products that meet the customers’ needs and so on.

Although some might think that cost of quality is an extra cost a business incurs associated with providing quality products or services, the ‘cost of quality’ can be seen as simply ‘doing business’: BUSINESS (PROFIT/SUCCESS) = CUSTOMER PRICE – COST OF DOING BUSINESS

There are costs associated with doing business, such as people, infrastructure, and departmental costs (eg, marketing, sales, engineering, new product introduction (NPI), manufacturing, support, finance, management). Also IT, tools, materials and process costs. However, some of these are often included as ‘costs of quality.’

Why extract some elements and label them as the cost of quality? ‘Cost of quality’ actually equals ‘cost of doing business’ and is in fact all the costs of the business in creating and selling products and services.

Another assumption is that astute businesses will look to continually review business’ processes, to address deficiencies and seek improvements, to ensure quality, financial success, and to ensure their societal/environmental impact is positive. Hence trying to reduce cost of doing business.

However, there is a cost category that needs to be closely monitored and vigorously addressed. That is the cost of non-quality (CONQ).

CONQ occurs when the design or application of the business’ processes have failed. For example:

- Sales forecast errors impacting manufacturing stock levels.

- Marketing release before product availability.

- Design release before test defect resolution.

- Poor design for manufacture/support.

- Manufacturing errors/design errors.

- In-house and in-field failures.

- Governance failures (management, audit and review action).

Think of recent major quality issues: Northern Rail (releasing train timetables before they were ready) and Carillion (governance and third party audit failures).

So, in reality: BUSINESS [PROFIT/SUCCESS] = CUSTOMER PRICE – COST OF DOING BUSINESS – CONQ

Focusing on the cost of non-quality, enables you to expand your thinking into all business areas to identify these costs of non-quality. After all, everything the business does impacts the quality of product or service and society.

As a starter: Next time you get another operating system update for your laptop or smartphone and think: “Good! I’m getting an update to keep me safe and give me more functionality”. Read the small print that says “…bug fixes…” and ask yourself why the software was released with bugs in it in the first place? Who knows what the CONQ is?

The cost of non-quality model

If you put cost of quality on the shelf, you replace it with the CONQ.

To do that you should examine three questions:

- Where do CONQs come from?

- How and when might they manifest themselves?

- How do we measure them?

- How do we monitor to prevent them?

Quality World

Get the latest news, interviews and features on quality in our industry leading magazine.